Shots and cuts need each other. They are cinema's primal handmaidens. The shots, as moments of luminous accommodation, ripen and expand and are popped like soap bubbles by the cut.

-- Nathaniel Dorsky, Devotional Cinema

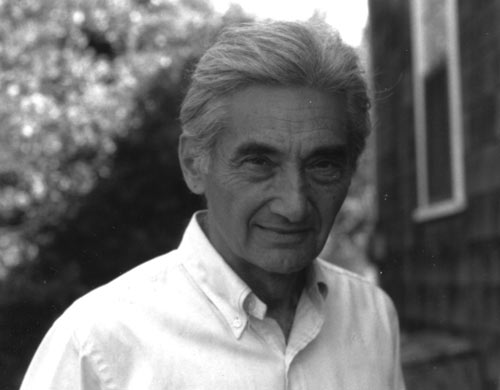

When experimental filmmaker Nathaniel Dorsky spoke last year at a screening in San Francisco, he described his mysterious form of filmmaking as a constant effort to prevent his work from "collapsing into meaning."

I love that. Narrative filmmakers work hard to tell stories visually, to make movies that have a literal meaning, even if that meaning is just a sequence of events in an action thriller: one man is stalking another and intends to shoot him. Or: that woman is annoyed by that child.

But half the work of constructing a film's meaning belongs to the viewers. By now, we all know how movies work. We know that two shots in succession fit together somehow. They're side-by-side because they're two views of the same building or two sides of a conversation. Even a bad film may meet the requirements of film grammar, the way a disaster-ridden wedding may still come off OK, if only because every attendee is a veteran of such events. The crowd propels things forward by supplying missing details, by collapsing the gaps into something that makes sense.

Many of Dorsky's non-narrative shorts are shot on the streets of San Francisco, but his goal isn't to create a travelogue or city symphony. San Francisco is just the raw material, so he constantly works against traditional cinematic language and against the viewer's natural tendency to see the object that his camera was pointed at instead of the color and shapes on the celluloid. His films aren't meaningless, but if they succeed it's because, rather than capturing a beautiful world, they undulate with a beauty of their own, one that reflects the world of the filmmaker but doesn't seek to contain it. A film that shows the Golden Gate Bridge may disappear when the bridge becomes the object of interest. Dorsky's films don't disappear; they appear.

Devotional Cinema, which grew out of a talk that Dorsky gave at Princeton in 2001, contains the ideas of someone who's thought about how and why films work, at a poetic-physical level. He considers not just experimental films but popular narrative films, too, and like his visual work, his text is crisp, spare, and gives me new ways to see movies.

The quality of light, as experienced in film, is intermittent. At sound speed there are twenty-four images a second, each about a fiftieth of a second in duration, alternating with an equivalent period of black. So the film we are watching is not actually a solid thing. It only appears to be solid.

On a visceral level, the intermittent quality of film is close to the way we experience the world. We don't experience a solid continuum of existence.

We sleep. We wake. We lose ourselves in thought. The traffic light turns green, popping the dream like a soap bubble. We reawaken to our surroundings. We turn our heads and see not a smooth pan but a series of jump cuts. "Intermittence penetrates to the very core of our being, and film vibrates in a way that is close to this core."