After jotting down some initial impressions of Claire Denis' wonderful, warm-hearted new film, I sat down for a conversation with Denis in Toronto. As Stephen Holden wrote in the New York Times recently, 35 Shots of Rum is "a movie of few words and little psychology that relies mostly on the physical vocabulary of faces and bodies to convey feelings too complex to be verbalized."

That's often true of Denis' films, and when I talked with her I found that this one has a very personal connection, as well. She spoke about the great Japanese filmmaker Yasujiro Ozu, about her grandfather, and about the interplay of work and family that appears in Ozu's films, in her own film, and even in her band of regular collaborators.

35 Shots of Rum plays March 13 and 15 at the Walter Reade Theatre in New York as part of the Rendez-Vous with French Cinema series.

Robert Davis: I saw your film yesterday for the first time, and I'm going to try to see it once more before I leave Toronto, just because I always feel like your films take a little bit of time. I like to figure out how to watch them. It's such a beautiful movie.

And what I discovered as I was watching is that it's an homage to Late Spring and Ozu!

Claire Denis: Yes. [smiles] I think I would not have been pushed or—

I've been dreaming for many years of making an homage to Ozu, and this particular film was possible for me to use as an homage to Ozu, because actually it's the story of my grandfather and my mother. She was raised by her father. And once I took her to see a retrospective of Ozu, and she really had a sort of shock to see that film [Late Spring]. That was like maybe ten, fifteen years ago, and I told her, "Maybe, once, I will try to make a film like that for you."

On the other hand I was a little bit afraid, and when I saw Hou Hsiao-hsien's film, the film he made in Japan—

RD: Café Lumière?

CD: Café Lumière, the homage, I thought maybe it's simpler to make an homage to Ozu. Maybe my shyness should be reconsidered. Maybe it's possible.

RD: What was the fear, do you think? Just that he's a master, that he—?

CD: No, my fear was that I'd be fulfilled with my love for his film and therefore not create a real relationship with my film. I realized this was a little bit stupid, because the minute I was in the film and with my characters and actors, I can't say I forgot Ozu, but on the other hand I was concerned by that story, those characters.

RD: One of the things I've always loved about Late Spring is that it feels completely foreign to my life, and yet it grabs ahold of me anyway. Having grown up in the U.S. at the end of the twentieth century, our relationships to our parents aren't like the one between the father and daughter in Late Spring. We have convenience foods and appliances so that dads who haven't been cooking their whole lives could probably figure out how to get by on their own. But you've found a contemporary way to retell the story. In fact those appliances become a touchstone in the movie.

CD: In a way I was helped by the fact that I was sort of growing as a stranger in France. But my grandfather, the widower, the father of my mother, came from Brazil. And when I was a child I remember everything he did, even the way he cooked — he enjoyed cooking for instance — or he had sort of rituals that were his own. And in my mind I always imagined it's because he's Brazilian, because he was so different from my other grandparents, the parents of my father, who were petit bourgeois French.

This grandfather was for me a sort of— he was a special man, very attractive, and I know that my mother, she's an old lady now, but she can still tell me that she was not raised like a little French girl. She was raised in the suburbs of Paris, [but] she was from another world because of him. So maybe also that's why she was so touched by Late Spring.

One of the things that put me into an Ozu frame of mind early in the film is a very Ozu-like series of shots in the apartment that Joséphine shares with her father, Lionel. They're simple static shots of domestic grids. The camera isn't low like it would be in Ozu — nobody's seated on the floor — but there are echoes of his films, the way the father rings the bell before coming in, the way the daughter smiles at the sound, the way he enters with a rice cooker, the way his daughter greets him, brings him his slippers, and shares a meal with him, and the way the interior space is shown in two or three camera setups linked together simply and efficiently.

Shortly after that sequence, the camera mysteriously tracks toward the empty entryway, a slow and subtle forward movement toward the front door, something Ozu himself would never have done. And then the camera pans left to connect the entryway to the kitchen area, separating the film from Ozu in a way that highlights the allusion and underscores the visual resemblance, almost like a comment on the composition.

There's a similar tracking shot a few minutes later in another hallway, just outside the apartment, when their neighbor Noé (Grégoire Colin) comes home to the same building and hears music emanating from the home of the father and daughter. The hallway is dark, but there's light coming from under their door. He pauses to listen for a moment, and Denis draws him toward their door with a tracking shot (Is it a subjective shot? Might he knock to say hello? Is he thinking of Joséphine?), but he doesn't follow. He turns to go toward his own apartment and stumbles on a bike in the dark hallway.

These two tracking shots, the only ones like them in the film, are exact opposites, pointed at opposite sides of the same door.

The film's repeated question is: Do I stay or do I go?

RD: Your movie is filled with fragments of families. All of the families in the movie are partial.

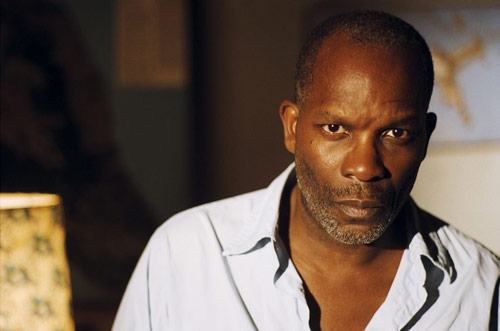

CD: Because you mentioned the word family, I must say that a long time ago, for a very different reason, I thought Alex Descas, who I met twenty-two years ago when he was a very young actor— I told him, "I have the feeling I'm going to work often with you, because there is something in you that is so calm, that gives me, helps me to create a character with you. You're a mysterious guy." Like Chishu Ryu was [an actor who appeared in many of Ozu's films, often playing a father]. But he was young, not yet a father, you know? But a sort of Chishu Ryu. Because in Ozu's films this figure of the father — even when it's not interpreted by Chishu Ryu, but mostly by him — I think it also described the respect or the relationship, I'm told, between Ozu and Chishu Ryu, which I think is great.

RD: Yeah. Chishu Ryu had to grow into that role of the father, too. Because they also started when he was very young, in those college movies.

CD: Yeah yeah yeah.

RD: He's so great in An Autumn Afternoon, which has pretty much the same story as Late Spring, and yet it has a completely different feeling.

CD: Yeah.

RD: I see some of that film in your movie, too, in the way Alex Descas hangs out at the bar, in the relationship he has with his co-workers.

CD: Yeah. Because in a way, if I consider the real story my mother and my grandfather— Because they were a sort of couple. My mother left her father when she met my father and created her own family, but there was always this, not regret but sort of mystery of her childhood, the couple she had created with her father, their rituals. And in their rituals there was a real split organization between work and being at home, you know?

And I think this is also true for Ozu. People's jobs are not just a decoration in the film. "Let's say he's a lawyer." No. It's normal people with normal jobs, and they have to go to work, they come back from work, you see the place where they work, and it's very important for the character that the audience is informed of the kind of job. And very often in Ozu's films the problems that occur during work time might reflect on private life at home, you know?

I think Ozu's characters are often sort of afraid that they might lose that job, you know? They are fragile, also, in their job. They are not the boss or— And they're only solid in their relationships, in a way, you know? In what they try to forge out of their life.

RD: Alex Descas's job in your movie is— he drives a commuter train, and so we see him doing that a lot, and we can tell that he's thinking about his day and thinking about his daughter while he's working. We get lots of shots of the tracks, not just a single track going into the distance but many different tracks, and you don't know which direction his train will go, necessarily.

CD: When I did location scouting I was very intrigued by the life of a train driver in the suburbs, and when I did location scouting I realized the strength and the power of being there, driving with the tracks, going and going and going. It's so hypnotic, and also it encourages anyone to introspect. It's immediate. And when I realized that, I started asking questions to the real drivers, and easily they agreed, completely. They were alone all day or night and they said, When we have a problem in our private life, sometimes it's hard because it's like a loop coming back, like the tracks, you know?

RD: One of the interesting things about your previous movie, The Intruder, was that you seemed to blend dreams and reality, with no clear distinction between them. That happens only a few times in the new movie, but one of them is a horse that's galloping along the tracks, carrying the father and daughter. That does seem like something that's going through Lionel's mind.

CD: This was something I did because his dead wife was German, and there was this plan for father and daughter to go to Germany. And I remembered this lied [Schubert's "Der Erlkonig"] — my version is sung by Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau — about the child taken by his father through the forest because the child has a high fever. It's a Goethe poem and it's Schubert who made the music, and it's a song about this father holding his child and so afraid that he's maybe not able to save, not strong enough to save the life of the child, you know?

Somehow I wanted— I loved that lied so much. It's a poem. It's like a prayer. Oh, my child, my kind, please don't die. It's full of fear and anxiety of....

I think it was always in my mind that being a father, especially of one child that he will take care of on his own, makes her in his mind in more danger than if he has a wife and a few children. The danger is that he's the only one to protect her, so I think he has raised this daughter, but so many nights he has been afraid because she's coughing or she's a little bit late or— you know?

RD: When they go to Germany, Joséphine's aunt almost seems a little bit theatrical in the way she describes what happened. It's an interesting performance.

CD: Ingrid Caven is Ingrid Caven, no? You— I would not— I love her the way it is. I thought the way she— She's like a queen. In my mind she is a queen.

RD: And Alex Descas, you mentioned that he's a mystery. I love to watch his face, and I love the way you linger on his face, especially the scene where the characters dance. Dancing is so important in your movies. And your musical choice in this case is from The Commodores, playing on the cafe's jukebox.

CD: Important, yeah. [pauses] The concert that they all want to go to, in my mind it was Prince coming back to France, you know? So I had a song by Prince that they were listening to in the car, going to the concert, but by the time we started reaching the company and everything it was too late to be ready for Venice and probably too expensive, I guess.

The song I chose was "The Little Red Corvette."

RD: Oh yeah? [laughs]

CD: [smiles. pauses.] Then in the cafe, I thought it was the moment where they were so wet. And drained by this rain. And sort of—

Lionel is so fed up with Gabrielle and going out and enjoying [the evening] like a family, you know. Actually, he's the kind of guy who would rather stay home, but OK. And suddenly you realize maybe it's an important moment because he could sort of hint that he's a free person, that he can choose [snaps her fingers] to pick up a woman, that he also has a private life and desire. And maybe for his daughter to realize they do not belong so much to each other. And also he's— I think he doesn't like when Noé is touching her hair. It's painful for him, but he wants to throw the dice, I think.

RD: Yeah.

CD: So I thought, if this is sort of two or three scenes to express that, it's no good, because in life sometimes things happen like that so I wanted to make it like [snap] in one moment. It's unexpected, they were supposed to go to the concert, and suddenly something happened. Not big, but for them it's big.

RD: Yeah. It's an important turn.

CD: [nods] Mm hmm.

RD: The score of the film is also very important.

CD: Yeah, it is. Stuart.

RD: He's great. [Stuart Staples, leader of The Tindersticks] What instruction did you give him?

CD: Oh, only the script. He read the script and as usual he's one of the first to know. And before we start shooting he moved from England, now he lives in France, and one day he told me— we were just starting the editing and I showed him some dailies, and he said I love the track. I said me too.

And one day he said, I have a little tune, I'm not sure, I think you won't like it.

And I told him, Yes maybe there's not so much space for music in the film. (I was sort of joking.) And I heard that first tune, and I said, But this is almost like an old French song, it's so weird, you made it, you—

And then I really wanted the guitar, too, to be there in the tunnels and everything, and— I mean I don't have to speak with Stuart, you know? Stuart can read me. I think he understands films sometimes [pause] before me, you know? Because while editing it's a sort of digging and digging and digging, and I think Stuart sees immediately where he is at, you know?

When I say digging, in this film it was not digging, it was easy editing, actually. Very simple. But I think Stuart was in synchronicity with us.

RD: Of course you've worked with the Tindersticks before and you've worked with many of the people in this cast before and Jean-Pol Fargeau and Agnès Godard [her screenwriting partner and director of photography, respectively]. You must have a close working relationship to work together so often.

CD: Yeah. I would— You know, it's not a family, in a way. Because it's more like— if I take the example of father and daughter, it's a little bit like a ritual, too. Because I would hate people to feel we are the family and they cannot say no [about joining the next project], you know. I want everyone to be free, but the ritual is "are you ready for this one? Are you in?" you know? It's like, let's try, you know?

RD: Like getting the band back together.

CD: Yeah, uh huh.

RD: Have people said no? Do they say no?

CD: No. No. [pause] No. Maybe, I don't know, sometimes I think they—

Stuart, I know— Because Stuart, he really— I think he likes me. So I think even if it's difficult, like The Intruder, or— Stuart doesn't like to make music for films, you know? He likes— We like to work together, which is slightly different, you know what I mean?

RD: Yeah.

CD: So it's strange, it's the coincidence of two people meeting, and so different, Stuart and me. We are completely different, but we so often feel things the same way, you know, although we are so opposed, by culture by sex by—

I think Agnès feels that we are not giving ourselves security by working together. She understands that by working together we are always trying not to do the same thing again and again, so we try always to approach the project, not with a new angle, we're not trying to improve or whatever. We try to make it a sort of— we want to experience together, we want to try together, and that's important for us. Otherwise it's boring. I think I try harder with Agnès and she tries harder with me. With others sometimes— She's a talented DP, but together we are more questioning filmmaking than questioning light and frame and, you know?

RD: I like the way she shot the tracks with a handheld camera. It seems like it would be obvious to kind of anchor the camera to the train and let it go, but—

CD: [shakes her head]

RD: with a handheld camera I'm never sure where we're going next, I feel uncertain—

CD: No, because we want it to be Lionel, a subjective shot, you know?

RD: So for your next film, White Material, you've worked with a different screenwriter and with Isabelle Huppert. It feels like a different— does it feel like a different—

CD: Yeah, I think it looks very much like one of her films. [laughs] No, Isabelle was a big pleasure for me, and Agnès could not make it because her mother was dying. So I worked with another DP which also was a great experience for me, and I'm editing the film now.

RD: One person we haven't mentioned yet is Grégoire Colin. One difference from Late Spring is that he does get the girl in the end. He's also a sort of free spirit, and yet he's anchored to this place and this apartment, and it can't just be because of his cat, you know [laughs].

CD: No no no no, of course. He is really [pause] in love, I think. I don't think she is sure she's in love with him, but that's another story.

RD: Uh huh. And the other woman in the film—

CD: Gabrielle.

RD: Gabrielle, right. I think it's an important bit of dialogue at the end. She's asking Lionel, Who's going to do her hair? Of course it tells us there's something coming, and we don't know what, but also his response is important: Well, she's fine on her own.

CD: Yeah, yeah. I like this actress Nicole Dogué very much. She's not a movie actress, she's mostly in the theater. I really enjoy working with her.

Did you feel— I read something in the newspaper— Did you feel something about all the characters being black, or did you forget it?

RD: I didn't think about that, I—

CD: Yeah, OK I'm happy with that. Because I read things about— a statement— Of course, in a way, yes. But I think it's better to forget it while watching the film.

RD: Yeah. If I stop to think about it, I guess it's important to their— to the way they all come from different places, and go to different places, and she has a German mother, a white mother. It's an interesting detail, but I didn't think about it while I was watching.

CD: Mm hmm. Thank you.

UPDATE 4-14-09: Within the space of 24 hours, Darren Hughes and I talked separately with Claire Denis about some of the same things. But each of us got different sides of her stories. I think Darren's interview is a nice companion to mine (and vice-versa), and it has just been posted at Senses of Cinema, and a fun addendum can be found at Darren's site, Long Pauses.

Martha at What is This Light has a very nice post about 35 Shots of Rum. And here are Ryland Walker Knight's first impressions.

This might be my favorite part: "No. No. [pause] No. Maybe, I don't know, sometimes . . ." I think you and I talked to her on the same day, and it looks like we asked a couple of the same questions, but it was obvious then and it's obvious now that she's listening, thinking, and responding to the interviewer rather than just rehearsing her talking points. I can't wait to see this again.

Yeah, and I don't think the transcript really captures her slow way of talking, the way she considers each question and allows herself to think during the interview. I liked comparing notes with you the next day, especially to discover that we -- that she -- talked about such different things, even though we started from some of the same kernels.

I'll link to Senses of Cinema whenever yours is up; they'll be fun to read together.

Thanks so much for this truly insightful interview.

This is great. And thanks for the links, Rob. As you may know by now, my full-length essay is now up at The Auteurs. Lucky me: I get a 1:30 showing to lift my spirits.

Cool. Here's the link.

Thank you for your post--and for a brilliant interview. I saw the 1:30 Walter Reade screening and was hoping C.D. would be there. Cafe Lumiere and bits of L'Intrus and Beau Travail were on my mind throughout--what a gorgeously shot film. And very surprisingly and touchingly comedic for Denis--the closing and opening Frenchified T-sticks accordion music, the fart, the cat, the family pushing the car in the rain, the generic resolution of the marriage at the end. I was blown away by how much was narrated through bodies and relationships in motion in the night bar scene--the nape of Gabrielle's neck and back, Lionel reaching for the restaurant host's hand, the moment Josephine pushes Neo away but still holds on and jerks him into the chair--I will never hear that baseline of Nightshift the same again.

I can see why CD doesn't want to overemphasize the all-black cast in the way that American identity politics can flatten out such things; but I do think the portrayal of immigrant working life, the inclusion of Josephine's school scenes and the students of color strikes was important for evoking the fabric of a still-postcolonial France that often is not shown in film--and this is central to the theme of diaspora's vibrancy and 'partial families' that you mention. And non-conventional families given much dignity and hope here--of how people belong, to each other, to place, to being in and out of place.

Is Dennis Lim cribbing from my almost-one-year-old interview for his latest New York Times piece?

(I'm kidding. Most of these topics are obvious and fall naturally from any discussion of Denis and this film. I'm actually really glad to see her written up in the Times.)

By the way, someone on the Criterion Forum recently took issue with my comment that Ozu would not have tracked through interiors the way Denis does briefly in 35 Shots of Rum. Here's my response.