The early criticism of Oliver Stone's W. has centered around its lack of ideas, and indeed it's a veritable void, another entry in a catalog of fictional films about the Iraq war that haven't benefited from time and reflection.

It is the funniest of those films, and seems the least angry, but it doesn't function as commentary or insight, and more strikingly it doesn't function as a character study, even a fictional one. While the performances -- by Josh Brolin, Elizabeth Banks, Richard Dreyfuss, Scott Glenn, Thandie Newton, and others -- are enjoyable to watch, it's hard to imagine this Condoleezza Rice sharing a scene with this George H. W. Bush. She's in a broad comedy, but he stepped out of an earnest TV melodrama about fathers and sons. They don't share a scene, but the glue between them is W himself whose outlines are left hazy so as to coerce the film's disparate modes into coexistence. On the outside, he's a face-feeding, shallow-thinking, attention-deficit-suffering plunger. On the inside, well that's anybody's guess.

Screenwriter Stanley Weiser seems to have assembled the script from notecards containing memorable phrases from recent American history. The greatest hits. "Fool me once ... can't get fooled again." "Slam dunk." "We know where [the WMD's] are. They're in the area around Tikrit and Baghdad and east, west, south and north somewhat." He hasn't put the quotations where they belong in history; he's scattered them into the story like he's playing a parlor game, a cute corpse, not terribly exquisite. In this film, Rumsfeld makes his claims about the location of the WMD's not on TV but in the war room with Bush, Powell, Cheney, Franks, et. al. Instead of waving his hands, he waves a laser pointer.

These aren't factual errors; they're a deliberately ahistorical juggling of familiar iconography, and yet this shuffling presumes little difference between how these people talked to each other and how they talked to the public, which is wrong, dead wrong, maybe even fundamentally disqualifying. Would any general tasked with finding the WMD's sit quietly across the table from someone who told him he knew where they were? It's odd enough that George Stephanopoulos did it, but TV lights do strange things to people.

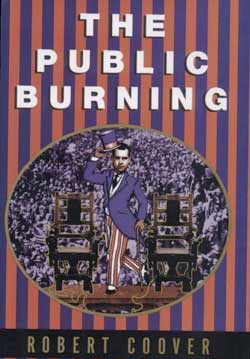

My benchmark for shuffled iconography is, and may forever be, Robert Coover's dazzling novel about Vice President Richard Nixon called The Public Burning, a novel whose continued relevance would be depressing if the book weren't such a fun read. Coover's absurd blend of Americana may be delirious and profane, but it's a chaos so controlled, so deeply in-tune with the collective psyche of America, that watching news reports amid very real chaos -- from 9/11 to Hurricane Katrina -- brings it flashing back to the front of my brain, without fail.

But The Public Burning isn't just an example of sharp satire. It's also a dense work of wicked scholarship. Coover's fictional Nixon spends much of his time thinking about the similarities between his life and Julius Rosenberg's, an inspired biographical braid that presumably required Coover to spend a year or two inside the heads of real people. How can we ever repay him?

I don't think Oliver Stone has spent much time inside the head of George W. Bush or the heads of his other characters. (In TV interviews, Stone regularly refers to Rumsfeld as "Rumsfield.") In the film's climax, when George W. is asked by reporters whether he's made any mistakes -- as the real President famously was -- I'm less sure what the caricature is going to say than I was the real President. The real W was going to figure out a way to say something self-deprecating while yielding not an inch to his political enemies. Stammering for an eternity showed political unpreparedness, not introspection. That's my guess.

When Stone's George W. pauses, he imagines he's standing in the Texas Rangers' center field. It's a far more sympathetic view than mine. He's a man unsure of himself, a man out of his element, perhaps a regretful man, a man who wants to give the question a real answer but isn't sure what to say.

That's one way to take it. The other -- the one I can't shake -- is that W isn't sure what to say because Stone and Weiser don't have any idea what he's thinking. They give us a couple hours from his life, presumably key moments of hazing and failure, trial by fire and trial by father, and in the end they arrive at a tremendous void. Maybe that's Stone's point, but such a conclusion works better as a sendup of biopics than it does a dissection of the thought processes that led to a lengthy and expensive war. As someone who generally dislikes biopics, I welcome such a sendup, and I probably laughed most when this biopic seemed fake. But if dissection was the aim, vagueness ending in void isn't very plausible or helpful. On a good night, you'll find five minutes on The Daily Show with better intuition and funnier jokes than the whole of W.

From the film's producers: 80 footnotes for W that expand on historical details referenced in the film.